Design Focus: Rose Uniacke

Understanding the historical significance of a space, a structure, and a site is the interior designer’s responsibility. No one does it better than Rose Uniacke.

Interior designer Rose Uniacke is the focus for this week’s Substack dispatch; this is essentially a profile on someone who walks the seam where creativity, personal knowledge, and business acumen all join together.

Early on, Rose Uniacke trained as a gilder, a furniture restorer, and a paint specialist before becoming an antique dealer.

“She uses muted colours, natural materials and comfortable upholstered furniture – often pieces she has designed herself – which she combines with antiques of outstanding quality from all over the world. The daughter of antique dealer Hilary Batstone, Rose was herself an antique dealer for many years until someone asked her to design their house.”

It helps to have grown up around the business of antiques (I did, too). An antique dealer-turned-interior designer, Rose Uniacke has quietly become one of the most sought-after professionals at work today, with high-profile clients — i.e., the Beckhams — and a complete portfolio of historically-fluent modern masterpieces all worth studying.

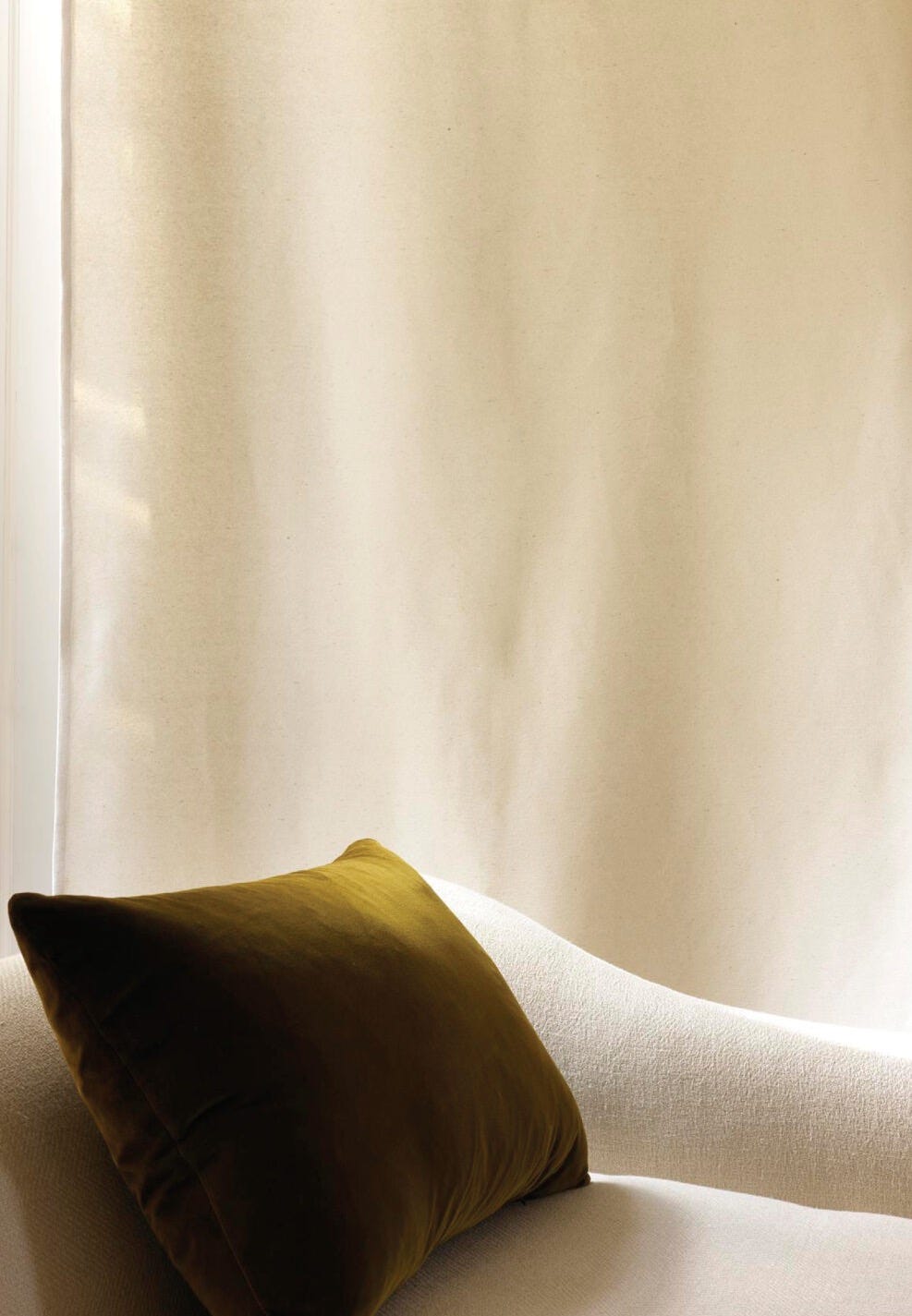

One of my favorite lessons from Rose Uniacke is her respect for emptiness. This sort of visual relief is the not-so-secret ingredient that makes her work feel serene but magnetically charged. Rose Uniacke lets negative space speak. Sanctuaries like Uniacke’s are what allow the inhabitants’ story to exist at the front and center, supported always by ample light and natural materials, never in competition with loud wallpapers or fussy tassels.

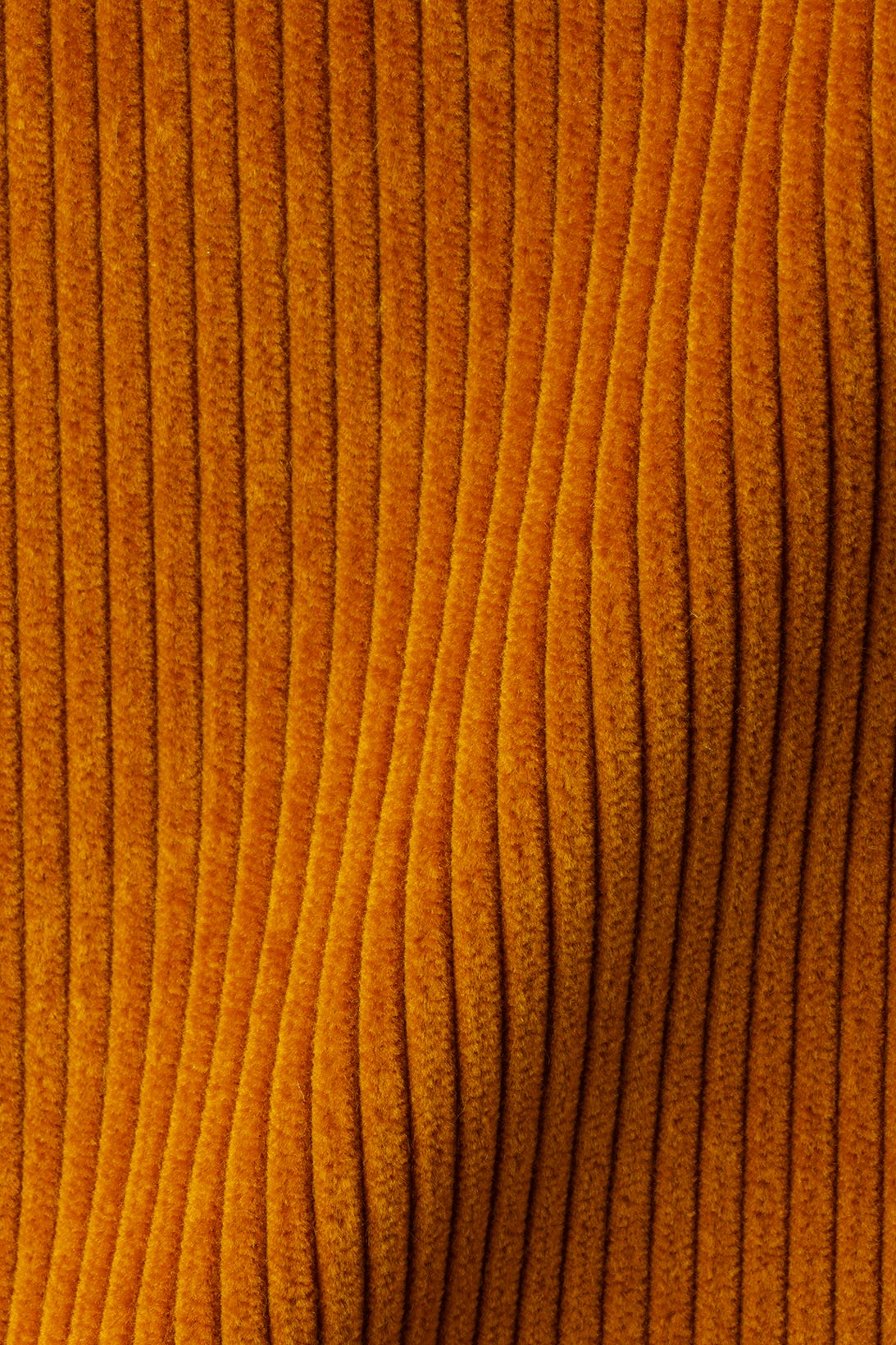

Throughout her body of work (which now includes fabric, paint, and furniture collections), Rose Uniacke gently joins classical elements in a modern, “minimalist vintage” sense that really speaks to this certain subcutaneous cultural longing we all have for more storytelling, more authenticity, and less noise.

Let’s take a closer look.

Pimlico Road Townhouse

Uniacke’s own residence on Pimlico Road in London is a project she couldn’t resist. Drenched with natural light and endowed with sky-high ceilings, this historic dwelling needed tremendous work. It was originally built as a studio and residence for Scottish portrait artist James Rannie Swinton, who commissioned architect George Morgan to design the house in the 1850s. This home already had what cannot be replicated. Its design is centered around a particular north-facing window that once allowed Swinton the space and light to craft some of his best portraiture.

Uniacke and her husband toured the house years ago, agreed it would take colossal effort to revive, then walked away, but could not put it down. They eventually purchased the property, then, in collaboration with architect Vincent Van Duysen, Uniacke completely breathed new life into a 19th-century relic.

“Once we’d stripped it, the house was sublime. It felt like an abandoned palazzo, with extraordinary volume in the rooms, and wonderful layers of distressed colours from years of decoration. I thought if we did a little bit of work, we could simply live in it and exist in the space in the raw, but as we started to restore and refresh everything, an interesting and exciting energy started to develop, and the restoration work became really important.”

— Rose Uniacke, excerpt from ‘Rose Uniacke at Home’ (Rizzoli)

In her book, “Rose Uniacke at Home”, Uniacke specifically talks about treating space lightly. It’s this careful treatment of a home — especially a home with large room “volume” — that makes Rose Uniacke’s spaces ideal for work, play, rest, and everyday life.

The Georgian Farmhouse

In the kitchen, writes Elfreda Pownall, “The rustic wooden table is complemented by rush-seated oak chairs designed by the Arts and Crafts furniture maker William Birch. Copper pans are suspended from a metal oval hanging rack overhead. Above the sink to the right of the Aga, a previously enclosed window has been restored.”

The Jane Hotel

Notably, the artwork in Rose Uniacke’s spaces often takes a background role. “My job was to create an environment in which the art worked in harmony, too. I didn’t want the art to stand out,” Uniacke has said of other projects.

Fabric

Paints

Rose Uniacke’s paint collection is comprised of natural, mineral-based paints created with sustainability at the forefront. 20 colors developed to align with Uniacke’s aesthetic, but also to achieve the industry’s highest ecological standards.

Furniture

This cast bronze stool designed by Rose Uniacke is a carbon copy of a time-worn antique stool made of wood. Using the technique of lost wax casting, Uniacke cleverly captures an exact image of a beloved stool, but in a much sturdier medium: bronze. If you think about the way both wood and bronze each develop inimitable patinas, Uniacke’s stool suddenly feels even more like intuitive alchemy.

“Every fissure, knock, dink and crack of the original piece is faithfully replicated in a Limited Edition of Twelve,” the R Hughes website says.

It’s not production for the sake of more product; Uniacke’s furniture serves as a practical extension of her craft.

Lighting

Thank you so much for reading! Next week, I’m excited to share all about my personal summer school this year — ‘Learning to Wallpaper’.

If you like what you’re seeing here, please make sure you subscribe to my weekly Substack and follow me on Instagram at @orahomecompany.

With love,

Eileen